What does it mean to be kind? From childhood, we are taught to understand kindness in terms of formal politeness, as a set of social norms that structure interactions. Amable Informal, the exhibition curated by Pilar Cruz at Fabra i Coats, Centre d’Art Contemporani, radically expands this notion: kindness is not only a disposition toward others but also a form of resistance, a practice of care, and a political gesture that challenges established structures.

According to the curator, kindness is present in the works as a critical praxis, as a way of doing and showing, as a starting point, or even as an inevitable consequence. In this way, the exhibition becomes a space for reflection, dialogue, and experimentation. Through experience, the perception of kindness as a mere formal or constrained gesture expands, revealing its presence in less tangible realms. It emerges as a critical tool to counteract the dynamics of a dystopian present—almost like small antidotes against pessimism and dystopia.

But what does kindness mean to the different artists featured in the exhibition? And how does it engage in dialogue with their works? The answers they provide create a map of kindness as a contested and expanding territory, inviting us not only to practice kindness but also to inhabit and think about it. Here, kindness unfolds as a space of listening, attention, and recognition of difference—manifesting in daily drawing as resistance against neoliberal performance, in the act of listening to one’s own body, or in a data visualization that reminds us that behind every number, there is a story.

Fito Conesa

“There is an idea throughout the exhibition that speaks of kindness in terms of accessibility, of being honest, of providing opportunity and space. In this sense, El nostre camí queda was always conceived, along with Olga Subirós and Pilar Cruz, as a space for listening and offering the possibility of stepping outside oneself, of moving into another time. For me, this directly relates to the idea of kindness as a risk we take and a way of being in the world—kindness as an almost resistant exercise.”

Enrique Radigales

“I understand kindness as paying attention to others and to the collective. That attention can also extend to objects or the ideals of others. In this framework, the Sensowifi bench represents a space where we acknowledge and respect that ‘infinite distance’ between beings, as proposed by Maurice Blanchot.”

Irene Pe

“The works in Un cuerpo doliente en un mundo herido speak of a kind of kindness directed toward one’s own body, offering listening and understanding in its illness, and then extending outward—to its surroundings, its wounds, and its pains. At the same time, practicing this cycle of experience, moving from the outside in and back out again, is itself a form of kindness. From illness, being kind means listening (to myself) in order to understand. Welcoming and accompanying whatever arises with attention, without judgment, with patience. Avoiding binary categories of good or bad, negative or positive. Coexisting with a spectrum of sensations and emotions. It means respecting (my) rhythms of activity and rest. Maintaining my critical capacity and dismantling the violence that neoliberal capitalism exerts upon bodies, lives, and territories—especially when it takes ableist forms. Recognizing that fragility, suffering, and wounds exist within all of us, that they are part of our lived experience, and that they do not devalue or make us disposable.”

Marc Herrero

“Kindness represents a place of belligerence against the unconscious resentment we hold socially. For me, it is like the act of drawing every day—a poetic gesture of defense against neoliberal performance. In this sense, my drawings are both poetic and urgent. We urgently need an imaginary of otherness. The mere act of imagining a different ‘other’ and allowing it to exist already constitutes a kind presence—an openness to new possibilities of life, beyond the deathly aura that capitalism imposes on existence.”

Luz Broto

“It is a disposition toward the other. Being willing to stand before the other, to recognize oneself and look into their eyes. My work has a lot to do with bridging distances, with connecting elements and people that were previously apart. We don’t really know who we see through the window every day.”

Julia Puyo

“For me, kindness is the result of feeling that everything is interconnected. It is an active way of being in the world, allowing us to express that we recognize (and care for, as best we can) that interdependence. Kindness also has a great advantage: once you begin to approach your actions with kindness, it is difficult to go back. Because once you apply it, how could you consciously choose to stop being kind?

When I learn that, so far this century, we have consumed as much copper as in all of human history, and that this consumption is increasing, I cannot help but think that we are devouring ourselves. Because if everything is part of the same ecosystem and is interconnected, the bite we take from material resources is a bite we take from ourselves. Degrowth is an invitation to disengage from the autopilot of modern life, an incitement to consider alternative ways of living—perhaps where we can say the same with less and live well by creating a different kind of balance.”

Radia Cava-ret

“Karaoke inmigrante dialogues with the notion of borders. It is a proposal that needs activation. It sleeps before and after collective catharsis. For us, kindness is the ability to love again. It is an ‘effective love,’ as Camila Torres said—a love nourished by the symbolic possibility of redistributing systemic violence through song and disillusionment.”

Blanca Gracia

“For me, kindness connects with the technique used in this piece: animation. It is a seemingly kind language, yet it serves to tell deeper social and political stories. This technique draws the viewer in with its appealing exterior, then captures their attention and compels them to learn more. To me, kindness evokes tenderness and care—not in the polite sense of the word, but as genuine care for the other, regardless of whether we know them or not. That is what I try to infuse into my characters—a sense of shelter, tenderness, and protection.”

Tau Luna Acosta

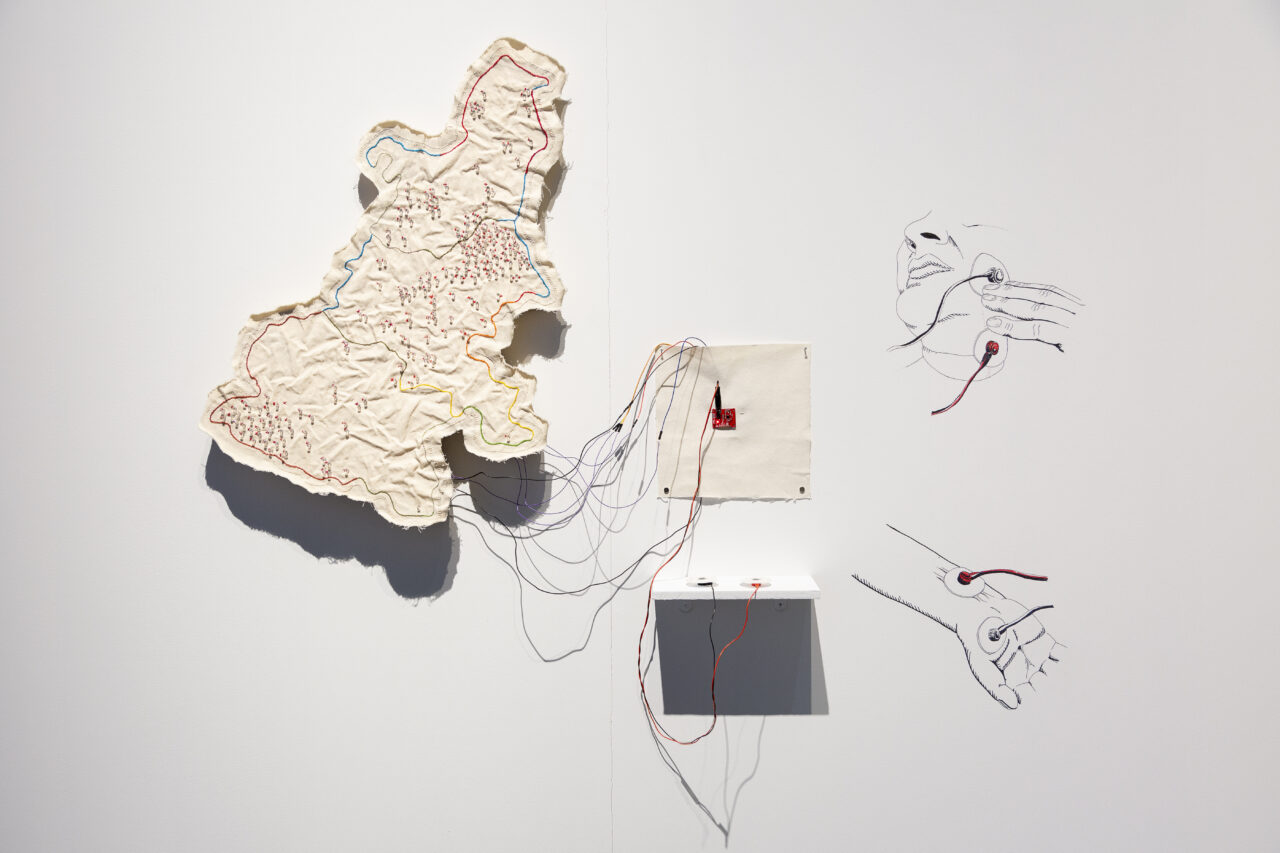

“My piece, Latencia, relates to kindness because, as an artist, I have chosen to engage with the harsh, violent, and difficult realities of my territory—realities that are nonetheless fundamental. I believe that artists and cultural workers have a responsibility to translate and communicate, even when dealing with issues that are painful to understand and accept. Sharing these realities through a piece that engages both body and sensitivity is an act of kindness.

The first act of kindness is defending the land for life. To me, community and land defenders are people who have dedicated their lives to love—the greatest act of love, which is resistance. It is kind to remember their names through embroidery, a slow practice. While we embroider, we talk, we sing, and we bring them into memory. They are remembered each time the map is activated through the body of a person connecting with it, even if they are not from the territory. Because to understand the dignity of a body, one does not need to belong to the same country or even fully grasp the issue—only to remember that we are all lives worthy of dignity, care, and memory. And they are brought back to memory every time the map is activated through the body of the people who connect with it, even if they are not from the territory, because I believe that to understand the dignity of a body, one does not have to be from the same country or even fully grasp the issue, but rather remember that we are all lives that deserve dignity, care, and remembrance.”

Bárbara Sánchez Barroso

“The version of Los nudos que anudamos that we are presenting in the exhibition is a slideshow documenting a performance I did alongside Adriana Vila Guevara in 2021 at ARBAR. It engages with the theme of the exhibition in many ways: during the performance, the audience who attended and chose to participate, under their own responsibility, had to take care of one another. There was an unspoken agreement to do so in silence, to wait for each other, to help one another descend steep slopes or navigate rocky paths. And there was this collective agreement to become one, through the ropes that connected them, embodying the idea that, instead of individual interest prevailing, the group would function as a single organism. For that to happen, a great deal of kindness was necessary.”

Xesca Salvà & Marc Villanueva

“For us, kindness has to do with allowing beings that are different from us to grow, but the most important aspect of El pensament salvatge is its engagement with difference. How can we be kind to what is incomprehensible, different, foreign, or even mysterious? There is something unsettling about this piece because bacteria and fungi have a bad reputation; they are ‘other’ beings, different from us, yet what is growing here is no different from what we have on our hands, in intimate contact with our skin, and present in the environment. This work poses an intriguing question about what constitutes ‘the other’—because although what grows in that Petri dish seems entirely alien to us as humans and is impossible to communicate with, a significant part of what makes us human is equally strange, unknown, and incommunicable. The biologists who advise us always say that three kilos of our body mass are bacteria, and they not only inhabit us but also form part of the world we move through.

The foundation of kindness is not just thinking about difference but acting in relation to it—engaging with what is not us. And if you think about it, we ourselves are essentially a swarm of differences (or, as one of the biologists we work with puts it, ‘a jar of bacteria’), then that is where our reflection on kindness emerges.

In El pensament salvatge, it is important for us to work with the awareness that, ultimately, we do not know how to control the beings growing inside the dish, nor is that what interests us. We start from the premise of slightly ‘misusing’ the scientific discourse, knowing that this Petri dish does not function in a strictly scientific sense. The inoculation could have been done in a laboratory, but the work is about that impossibility. We chose to perform the inoculation as a ritual, with people who join in that day, under uncontrolled conditions. For us, that is where life is found—within that soft space of approaching knowledge through kindness. A knowledge that is not rigid, authoritarian, objective, or inflexible, but rather a communal experience. And perhaps what truly matters is not so much our knowledge as human beings, but rather what is generated on a microbial level in that transfer—those beings that begin a life in a kind of paradise, even if it eventually collapses, as all things do…”

______

APROPOS consists of content created with a purpose in response to something happening in our artistic context. On this occasion, we collaborated with Pilar Cruz and Fabra i Coats. Centre d’Art Contemporani to delve deeper into the idea of kindness, which runs throughout the collective exhibition Amable Informal.

Photographs taken by Eva Carasol